Republished with permission by Vista, see original article here

Photo by Jeremy Bishop on Unsplash

Long after the UK had joined the European Union (on New Year’s Day, 1973) it was not uncommon to hear Brits tell me they were ‘going to Europe for their holiday’. To be fair, when I started visiting the Scandinavian countries, I heard people using similar language. I was completely thrown, however, when friends from Italy, Spain, and Greece, also told me they were ‘going to visit Europe’. This was confusing! Where did they think Europe was?

Other contributors to this edition of Vista have noted similar confusions about the nature of mission in Europe. Some see it as something done by Europeans in other places, not within Europe. African Christians, on the other hand, challenge their European sisters and brothers to think of Europe as precisely a mission field. They are shocked at Europe‘s descent into secularity and are not afraid to describe Europe as a post-Christian continent. Others might consider Europe a ‘dark’ continent.

But, if this is so, is Europe uniformly dark? What happens at its edges? Does the light that (apparently) shines more brightly in Asia or Africa, spill over into the parts of Europe that border these continents? More particularly, which Europe is darkened? The metaphor of ‘people walking in darkness’ is certainly biblical, but its use needs a little more care than is often shown in some of the examples found on mission agency websites and in their literature.

While some of our European contributors agree with the diaspora perspective, several of them express hopeful views. They acknowledge the challenge of secular humanism to the Gospel but point to signs of God at work, challenge Christians to bridge the cultural gap between church and European society, issue a call to make disciples of younger generations, and, as Alex Vlasin suggests, urgently find new ways to ‘voice the gospel’.

Evangelical authors, writing about Europe, have used a wider variety of biblical imagery over the last decade or so. David Smith (Mission After Christendom, 2003) suggests that Europeans are like the disciples on the Emmaus road, who have forgotten the Christian story. Jeff Fountain has described Europe as a ‘prodigal’ continent. Others, including Duncan Maclaren (Mission Implausible, 2004), suggest that belief in contemporary Europe is implausible. The mission of the church in Europe is to make faith credible through vital communities of Christians who live and demonstrate the plausibility of the beliefs they profess. The loss of Notre Dame cathedral, in Paris, was described by Mark Thiessen, in the Washington Post (24th April, 2019), as a reminder of the need to rebuild the European church using ‘living stones’ (1 Pet 2:4-5).

Broadening the imagery helps, but so too will expanding our vision of what constitutes Europe. If deciding which countries count as ’Europe’, and which don’t, is a tricky business, then it might be more helpful to talk about Europe in the plural, to accept that there are probably several different versions of Europe. This might then explain why there are some versions of Europe that we like and others that we don’t.

The sheer diversity reflected across the forty-seven member states of the European Council can be confusing, and is often seen in the wide differences of political history, language, religious heritage, cultural identity, climate, proximity, regional variation, political vision, economy, geography, industry, and so on. Lumping all 47 into the same ‘dark continent’ category seems either clumsy or lazy, and possibly both.

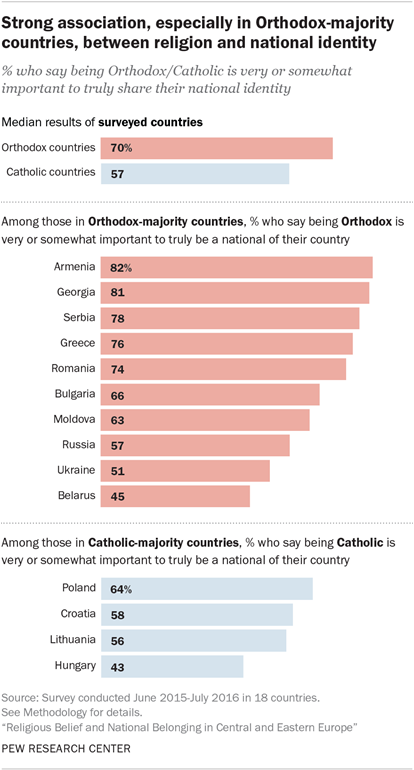

Of course, there are barely indisputable facts that European mission agencies and churches must face and, to be honest, many of them are painfully all too aware of the facts. The 2017 Pew Research report (Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe, 2017, p.5-6) noted that ‘Central and Eastern Europeans display relatively low levels of religious observance’ although it also reports that ‘religion has reasserted itself as an important part of individual and national identity’, and ‘solid majorities of adults across much of the region say they believe in God’. Maybe it’s better to say that Central and Eastern Europeans are not god-less, rather that they are not too concerned with what God might expect of them. This is the background for comments in this edition from Alex Vlasin, for example, that the churches of these regions often see themselves as insignificant, under-resourced, and subsequently determined to work in East-West partnerships.

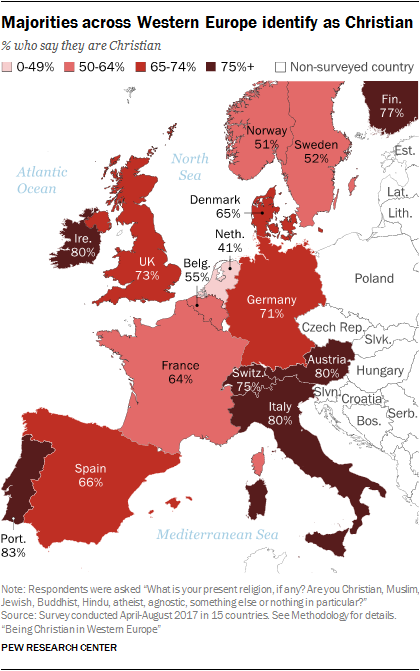

In Western Europe, the Pew Research report Being Christian in Western Europe (2018, p.7) describes European Christians as mostly non-practising rather than non-believing; ‘most adults surveyed still do consider themselves Christians, even if they seldom go to church. …non-practicing Christians […] make up the biggest share of the population across the region. In every country except Italy, they are more numerous than church-attending Christians.’

Across Europe, the greater majority of people who identify as ‘Christian’ are simply de-churched. Many of them were baptised as infants. Many of them are geographically close to a church where Sunday worship still happens. But, sadly, they’ve forgotten the Christian story; they’ve strayed from churches that have disillusioned, ignored, or betrayed them; they no longer find Christian faith plausible; they find Sunday worship boring, irrelevant, or unengaging.

Do these facts alone make Europe a ‘dark continent’ without distinction or difference? The biblical passages that refer to people ‘walking in darkness’ also refer to the light shining upon them. Wherever we imagine Europe begins and ends, even though it may be darkened, the light of Christ still shines there. De-churched Europeans may stumble in the darkness but the light of Christ has not been extinguished.

It’s possible that missionary efforts that are only directed towards rekindling the light of Christ through planting more new churches, misunderstand the nature of the missionary challenge in Europe. We may not like some of the ways that Europeans have chosen to work together (the EU, for instance?), and we may think these should be located on a scale somewhere between strange to oppressive, but when God’s people found themselves in similar situations, we read that they learned to ‘sing the Lord’s song’ in strange lands and though this was painful, they persisted. The early church also learned to live as pilgrims in a foreign land, a world that was not their home. This required a major reimagining of the world in which they had previously lived as fully engaged heathens and loyal subjects.

Maybe a deeper understanding of Europe will help missionaries avoid making a common mistake. That is, the mistake of assuming that they understand Europe without really studying and finding out more about it. Every one of the contributors to this edition of Vista shows the hard word of thinking carefully about Europe. They collectively underscore the need for new visions of Europe, for a reimagining of the Europe that we thought we knew. It might be dark in places but to consider it dark everywhere is unimaginative and shows a lack of vision and understanding.

Christian missionaries in and to Europe are called to engage the Gospel with a more appropriately imagined Europe; a Europe that is wonderfully yet frustratingly diverse. Europeans might believe they are Christians, but the central missionary challenge is to be the body of Christ in such a way that Christian faith is seen to be plausible, memorable, and transformative! To believe that is possible requires us to reimagine Europe!

Darrell has European-wide missionary experience and has been an ECMI Board Member since 2014.

He has been a pastor, a former National Mission Advisor to the Baptist Union GB, was a CMS(UK) mission partner serving as the Executive Researcher for the Conference of European Churches. He was the founding Director of the Nova Research Centre and Lecturer in European Mission. In early 2012 he relocated with his family to Australia, where he now works as the Director of Research at Whitley College, Melbourne.